Main Character Energy

A Network-Effect Approach to Business Futuring

Leaders really only need one thing, and it’s the hardest thing to get. The more senior they are, the more of it they need, and the harder it is to obtain.

The future.

Tomorrow is fascinating for leadership because that’s where all the change potential and decision space exist. Today is nearly gone, and yesterday is already irrelevant—unless it helps predict what’s coming next.

Companies use forecasting and planning to prepare for the future. Forecasting relies on past data to identify patterns that may appear again. Planning sets objectives and strategies to achieve desired outcomes based on those forecasts. But futuring attempts to push beyond this, using speculative methods to reduce uncertainty through weak signal detection and qualitative experimentation.

Systems like the Rohrbeck Maturity Model have shaped corporate strategy for decades, helping businesses understand their own organizational foresight capabilities. While these models provide valuable frameworks, they don’t tell leaders what to look for—only that signals are out there. Businesses now rely on AI-driven systems to scrape market signals and trends, but what exactly are these “civilian intelligence agencies” gathering?

Perhaps we can look to the military for answers.

Intelligence Isn’t Smart

During a recent visit to a Department of Defense information warfare facility, I discussed intelligence gathering across the military-industrial complex. One analyst remarked in frustration:

"There’s so much data—what’s it telling us?"

This gets to the heart of a major challenge. Intelligence analysis is not about simply collecting vast amounts of data—it’s about interpreting what that data means and how it informs decision-making. The same is true for business futuring.

The intelligence process is operational, not strategic. It reacts to the environment, identifies trends, and provides analysis to support decision-making. But it does not dictate the strategy itself. That distinction is important.

Businesses, much like military intelligence operations, often get lost in data collection. They track signals, monitor markets, and analyze trends, but they fail to see their own role within the system. They assume they are the protagonist of the story—when, in reality, the network dictates the outcome.

If traditional forecasting and intelligence analysis are inadequate for shaping the future, perhaps literature can provide a better model.

From Fiction to Fact

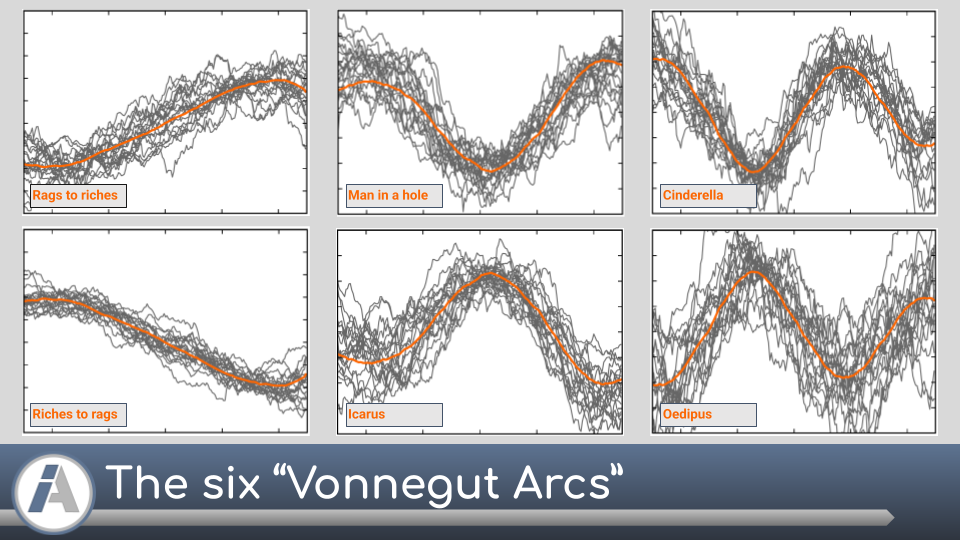

American novelist Kurt Vonnegut proposed that most stories follow one of six core emotional arcs:

Rags to riches (rise).

Riches to rags (fall).

Man in a hole (fall-rise).

Icarus (rise-fall).

Cinderella (rise-fall-rise).

Oedipus (fall-rise-fall).

A 2016 study from the University of Vermont analyzed 1,327 stories from Project Gutenberg’s fiction collection using natural language processing. The results confirmed Vonnegut’s theory: every single story fit within one of these six shapes. Shown below are the shapes of the “Vonnegut Arcs” in orange with how closely stories adhere to the pattern in grey.

(The entire study cited, Reagan, A.J., Mitchell, L., Kiley, D. et al. The emotional arcs of stories are dominated by six basic shapes. EPJ Data Sci. 5, 31 (2016), is available to read and download from SpringerOpen)

Why does this matter? Because storytelling isn’t just entertainment—it’s causative. The best narratives follow logical, causally linked progressions. If Chekhov’s gun is on the mantel in Act One, it must go off in Act Three. These arcs aren’t just patterns in fiction; they reflect real-world human dynamics.

And that means they also apply to business.

Why Narrative Arcs Hold at Scale

At an individual level, life is unpredictable—stories don’t always follow neat arcs. Sociopolitical scientist Brian Klaas captures this idea in his 2024 book FLUKE, writing:

"Reality doesn't have a narrative arc. We cram it into that form nonetheless, as our storytelling minds distort our view of the world."

Klaas’ observation bears out when we analyze individual experiences. Not every person or small business follows a clear rise-fall-rise trajectory. The sheer complexity of networks—relationships, chance, external shocks—introduces randomness at a micro level.

But at larger scales, when we analyze governments, militaries, multinational corporations, and global markets, the randomness begins to resolve into identifiable patterns.

The Vonnegut Arcs in Macro-Networks

At a macro-network level, historical forces, competitive pressures, and strategic decisions interact within predictable narrative constraints. That’s why, when analyzing long-term trajectories of nations, companies, or industries, we consistently find echoes of Vonnegut’s six arcs.

This is because:

Narratives emerge from relational actions. Businesses and states do not operate in isolation; their moves influence and are influenced by others, pulling them into recognizable patterns.

Competition and cooperation create structural inevitabilities. Whether in statecraft, business, or military affairs, actors are bound by game theory dynamics, forcing them into decision trees that narrow down potential story outcomes.

At scale, the noise cancels out, revealing the shape. While individuals and small enterprises might deviate, when we zoom out, patterns repeat across history, industries, and geopolitical shifts.

In other words, at the level of governments, militaries, and corporations, "narrative collapse" occurs, funneling strategic trajectories into a finite set of patterns.

Understanding this matters because businesses—like nations—are not exempt from narrative constraints. The arcs of industries and enterprises resolve in predictable ways, often determined by forces much larger than the organization itself.

No Small Parts—Only Small Businesses

It may sound deterministic, but companies take on archetypal roles—whether they realize it or not. Businesses rarely operate as singular protagonists; instead, they exist within complex narrative networks where success and failure hinge on recognizing the role they’ve assumed based on their interactions.

Markets are relationships, not competitions. Even as Blockbuster followed a "Riches to Rags" arc, it played the role of the “Stepmother” in Netflix’s Cinderella moment.

Blockbuster’s Mistakes:

- Rejected Netflix’s $50M acquisition offer, assuming streaming was irrelevant.

- Clung to outdated models (late fees, physical stores) while Netflix adapted to consumer behavior shifts.

- Made a late, half-hearted pivot to streaming but was already too entrenched in its old infrastructure.

In hindsight, the story seems obvious. But Blockbuster didn’t recognize the archetypal role it had begun to fulfill. It failed because it didn’t recognize the narrative unfolding around it.

Businesses Need to Understand:

- There is no single main character—they are one of many in a larger narrative, and the hero doesn’t always win.

- They earn their role(s) through actions—but in relation to the network narrative, not by their own self-perception.

- Arcs are predictable if you know what to look for.

- What arc(s) are at play within the network

- What archetypes(s) their business business fulfilling

- Archetypes interact with each other differently depending on the arc

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung theorized that certain archetypal roles are embedded within the collective human experience. American writer Joseph Campbell expanded on this, applying archetypes to story structure. These models surface at the macro and provide insight into why networks follow predictable paths—not because they are bound by fate, but because large-scale networks resolve into finite and predictable narrative structures.

The archetypes apply to network decisions and can be tracked to any actor over time, including businesses:

Archetypes & Indicators: Actions Define Role

In any given market, businesses take on functional roles that shape their trajectory—not because they declare themselves to be something, but because their actions define them as such. Companies do not choose their archetype; the network assigns it based on behavior, influence, and interaction. Recognizing these roles is critical to understanding industry dynamics, anticipating competitive shifts, and making strategic decisions before the narrative locks them into an unfavorable path.

The Hero is the company that pushes an industry forward—often at great risk to itself. Heroes redefine markets, not by merely innovating but by fundamentally challenging entrenched structures. They move fast, adapting to obstacles before their competitors even acknowledge them, and in doing so, they provoke strong reactions from incumbents. A Hero will be met with resistance from Shadows and Threshold Guardians, facing regulatory scrutiny, lawsuits, and counter-narratives designed to slow them down. Their impact extends beyond their own growth—Heroes create network effects, pulling in talent, investors, and infrastructure as industries orient themselves around the changes they introduce. When a Hero is at work, customers start expecting things that didn’t exist before, and competitors start chasing a moving target. But Heroes don’t always win—overextension, public backlash, or failure to consolidate gains can transform a Hero into a cautionary tale just as quickly as it propelled them to prominence.

The Mentor doesn't chase headlines, but without them, the industry collapses. They build the infrastructure that allows others to scale, often providing platforms, supply chains, or strategic knowledge that enable Heroes to emerge. A Mentor’s impact is seen in the companies that rise because of their support—those that integrate with their technology, rely on their logistics, or build upon their frameworks. Unlike Heroes, Mentors favor stability over high-risk transformation. They don’t disrupt industries; they make disruption possible by ensuring that foundational systems remain intact. They tend to form relationships across multiple players, working with Heroes, Shadows, and Tricksters alike. While Mentors may seem secure in their position, their greatest risk is being eclipsed by the very companies they enable—when a Hero no longer needs its Mentor, the Mentor is often the first to be left behind.

Threshold Guardians control access—to platforms, to customers, to markets. They set the rules, impose the fees, dictate compliance standards, and block new entrants who can’t meet their requirements. Guardians can take many forms—from government regulators who enforce antitrust laws to entrenched tech giants who make it difficult for competitors to gain traction. They are defensive actors, maintaining dominance by establishing barriers to entry that others must navigate. Some Guardians use legal and bureaucratic structures to slow innovation, while others acquire emerging competitors before they become threats. The more successful a Threshold Guardian is, the more likely they are to be targeted by Heroes and Tricksters who seek to bypass or dismantle their control. If they lean too hard on restriction without innovation, they risk becoming the villains of the story, inviting regulatory intervention or consumer backlash.

Heralds don’t shape industries directly—they shape how we perceive what’s coming next. They are the analysts, journalists, thought leaders, and institutions that identify, amplify, and predict major industry shifts before they happen. The power of a Herald is that they control the narrative about change. A well-timed prediction from a Herald can shift investor sentiment, redirect corporate strategy, and accelerate trends that might have taken years to unfold naturally. However, Heralds are not always right—they are as susceptible to hype cycles as anyone else, and misreading trends can lead businesses into costly miscalculations. Worse, when Heralds lose their objectivity and become participants rather than observers, they risk becoming market propagandists rather than independent analysts. Those who follow a Herald’s proclamations without critical evaluation may find themselves reacting to illusions rather than actual shifts.

Shadows are the market challengers. If the Hero is the company trying to redefine the market, the Shadow is the one trying to stop them. The Shadow can represent the entrenched power, the incumbent model, or the challenger fighting to impose a different vision of the future. They force Heroes to evolve by resisting their changes, either through direct competition or by leveraging existing infrastructure to counteract disruption. Shadows frequently launch legal challenges, counter-messaging campaigns, or alternative technologies designed to make Heroes seem unstable or unnecessary. They often hold deep brand loyalty or regulatory entrenchment, making them difficult to dislodge even when their model is under threat. A Shadow may start as a Hero that failed to adapt, but instead of fading away, it shifts into a defensive posture, leveraging its resources to resist the new wave of innovation. However, if a Shadow is too slow to evolve or underestimates its opponents, it risks becoming obsolete instead of a true counterforce.

Tricksters aren’t interested in following the rules of the system—they exist to break them. They introduce unexpected innovations, challenge authority, exploit loopholes, and leverage viral movements to disrupt industries in ways that traditional players aren’t prepared for. Tricksters thrive in chaos, often using controversy or cultural shifts to drive attention and engagement. They experiment with new business models, sometimes failing spectacularly, but sometimes changing the game entirely. Their unpredictability makes them difficult to counter because they aren’t playing by the same strategic frameworks as Heroes or Shadows. However, Tricksters also carry significant risk—many burn out before they can stabilize, and those that do succeed often struggle to transition into sustainable business models. If they survive long enough, Tricksters may evolve into Heroes—or they may become Shadows, defending the very structures they once sought to destroy.

Allies & Sidekicks aren’t the protagonists of the industry, but they help decide who wins. They exist in symbiotic relationships with larger players, supplying materials, manufacturing, or specialized services that allow Heroes and Shadows to operate. Their success is tied directly to the dominant players they support—when their Hero thrives, they thrive; when their Hero collapses, they are forced to adapt or perish. Allies often operate in niche but critical spaces, serving as the backbone of larger ecosystems. While they may seem stable, they must constantly navigate the shifting power structures of the network—aligning themselves with new players when old ones falter. Some Allies evolve into Threshold Guardians if they gain enough market control, while others remain essential but largely invisible enablers of industry-wide shifts.

Find Your Narrative, Your Information Advantage

For decades, businesses have approached futuring as if they were the main character in the marketplace. Strategies assume companies sit at the center, collecting weak signals from the environment and adapting accordingly.

Our bespoke futuring methodology, network-effect-based non-linear futuring, bounds the narrative landscape, analyzes the narrative terrain to determine the narrative arc structure, samples behavioral indicators of archetype, assigns time and role across network actors and models narrative outcome given change sets.

Businesses that understand their role and story arc can anticipate how the system will evolve before the next plot twist. The next chapter is being written. The question isn’t just who’s writing it—it’s whether you’ll shape the story or let the market write it for you.

Let’s talk about your future.

#IA

Steve's blogs are written by Steve and co-edited by Jack and Information Advantage Assistant, a GPT trained by Steve. If you're wondering how to get AI included into your workflow flow from content creation all the way to strategic campaign management and forecasting, reach out!