Doubling Down on Truth

How Perception, Language, and Cognition Shape “The” Truth

In January of this year, I was teaching a lesson on cognition and narrative to a group of senior public affairs practitioners at the Defense Information School. I shared an anecdote about how the perception of the color blue is linked to language, highlighting how our words shape how we see the world. For instance, some cultures historically couldn’t distinguish the color blue because their language didn’t have a word for it. (You can read more about those fascinating studies at Burnaway.)

Then, one of the students raised his hand and said, “I just don’t believe you. Their eyes are like ours. The blue was there; they saw the blue. Just because they didn’t have a word for what they were seeing doesn’t change the fact that they saw it.”

That simple statement revealed something much deeper—not just about color perception but about how we define reality and, more importantly, how we decide what to trust. In today’s world of information overload and divisive rhetoric, understanding this distinction is more important than ever. Let’s dive into what this means and how it affects our ability to build trust in an increasingly skeptical world.

Belief, Truth, and Perception: Where Do We Begin?

Let’s start with belief. In the English language, it’s a somewhat squishy concept. It can mean anything from religious conviction to a strongly held opinion to a fact-based truth, depending on how it’s used. The senior Air Force NCO who challenged my claim wasn’t questioning the credentials of the researchers or the integrity of their methods—he was questioning the truthiness of their findings. Something didn’t sit right with him. His instincts told him there was a flaw in the logic, even if he couldn’t fully articulate why.

The blue was blue, and the linguistic barrier couldn’t have changed what people physically saw—or could it? His reaction wasn’t just about color perception; it reflected a deeper struggle with how we define and process truth itself.

Ontology and Epistemology: How We Frame Reality

Two key philosophical concepts help us unpack this: ontology and epistemology.

- Ontology is the study of what exists—the nature of reality itself. Are things as they are, independent of us? Or does reality only exist because we perceive and give it meaning?

- Epistemology is the study of how we know what we know. What counts as knowledge, and how do we verify it?

To simplify:

- Objectivism (an ontological view) holds that there is an external reality that exists independently of our perceptions. Reality is out there, whether we recognize it or not.

- Subjectivism suggests that reality cannot be known apart from our subjective experiences. What exists, exists because we recognize and agree on it collectively.

Similarly, in epistemology:

- Positivism claims that truth can be discovered through observation and measurement—if it’s verifiable, it’s true.

- Interpretivism argues that knowledge is relative and shaped by our interactions and interpretations. Truth is constructed, not discovered.

Think of ontology as the actual terrain of a landscape, and epistemology as the map we use to navigate it. The terrain doesn’t change, but depending on how the map is drawn—or how we interpret it—our understanding of that terrain can vary wildly.

Theories of Truth: How We Decide What’s Real

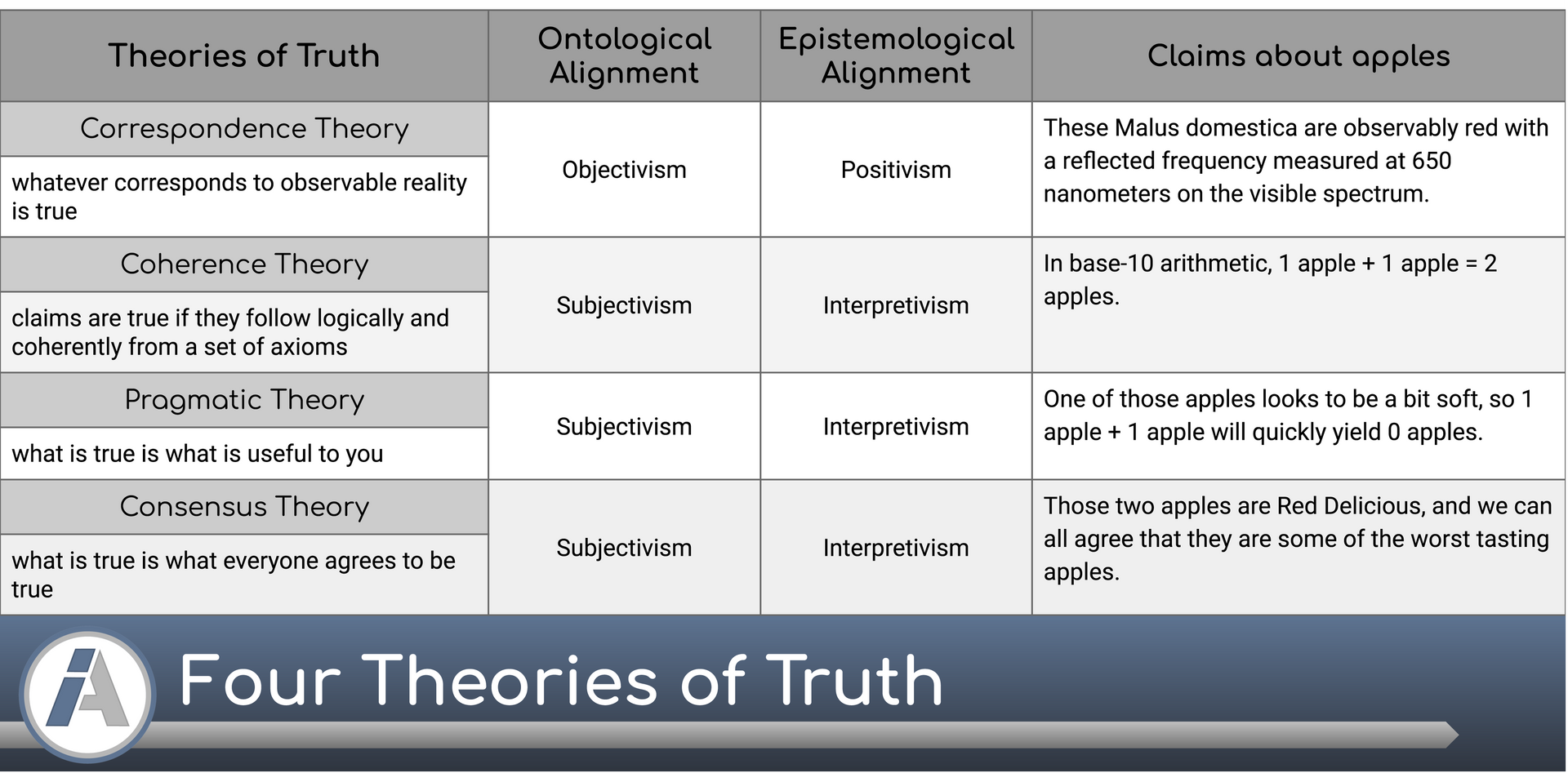

From these philosophical roots come several theories of truth. While there are many out there, four stand out as particularly useful for understanding how trust networks are formed in today’s information environment.

(By the way, if you agree about Red Delicious apples being the absolute worst, you’re in good company. Here’s a fun read from HuffPost on why they’re universally disliked.)

So, Why Didn’t He Believe Me?

When this senior leader said, “I just don’t believe you,” what he was really doing was positioning himself within one of these frameworks. Let's break down how this might look from different perspectives:

- A Modernist Perspectivism Interpretation (Correspondence Theory): The blue was there. It could be measured on the visible spectrum, and unless there was a physiological issue with their eyes, those people saw the blue. Facts are facts, independent of language or perception.

- A Symbolic Interactionism Interpretation (Consensus/Pragmatic Theory): This claim challenges how I structure my understanding of the world. Since it doesn’t fit my internal framework, and because I don’t yet trust the source (me), I’m skeptical. Until I have a reason to value your claim over my existing beliefs, I won’t accept it. Also, I’m not sure why we’re doing this in an advanced contingency public affairs course—this all seems a little sketchy.

The student believed he was operating from an objective standpoint, but in reality, his skepticism reflected a more subjective process—one influenced by trust, social dynamics, and personal frameworks.

How can I really know that? I’m not in the student’s head, and he’s not here giving a firsthand account. But even if his challenge was rooted in Correspondence Theory—focused on objective facts—it still arose through his subjective, emotional response. Something felt off, and that feeling led to skepticism. Whether trust was never established or momentarily broken, his reaction shows how even the pursuit of objective truth is filtered through personal experience.

Your Truth, My Truth, and Something In Between

We encounter these dilemmas in professional discourse and in the media on a near-daily basis. For instance, political strategist Scott Jennings recently dismissed WNBA player Caitlin Clark’s reflections on white privilege by saying, “There isn’t my truth or your truth, there’s just the truth.” It’s a soundbite that made the rounds, but it reveals a common misunderstanding of how truth operates. You can check it out on YouTube.

Jennings is appealing to Correspondence Theory—the idea that truth is objective and measurable. But Clark’s statement reflects a different kind of truth, one rooted in personal experience and social context. Both perspectives are valid, but they operate in different frameworks.

So what’s truth, really? And how do we know when something is true?

Based on the theories of truth, something can be true in one of four ways:

- If it is real (Correspondence)

- If it follows the rules (Coherence)

- If it is useful (Pragmatic)

- If “everyone” agrees it is (Consensus)

We sense truth through facts. A fact is the way we cognitively process and sense truth from untruth—and all the shades of gray in between. That’s why some truths feel black and white, while others exist in a murky in-between.

For example:

- Correspondence truths are pretty black and white. If something exists or can be measured, we recognize it as fact. But when something feels off—like a human-looking robot in the uncanny valley—our fact-sense kicks in to tell us something isn’t right.

- Consensus truths depend on social agreement. You might not be sure if a decision is right until you hear the group’s consensus, and that collective agreement helps solidify your perception of the truth.

- Pragmatic and Coherence truths rely on rules and utility. Some people are firmly rooted in systems that have always worked for them. Changing those systems challenges what they perceive as true. If the rules have always functioned effectively, they must be true—right?

How Do We Build Trust When We’re Rewriting Someone’s Reality?

This is the heart of the challenge. How do we build trust between groups when we’re essentially asking them to question their observable universe?

We have to show them that it can be rewritten.

In many organizations, we do things a certain way because “that’s how it’s always been done.” Over time, those routines become sacrosanct—and eventually, they become the very fabric of reality. People within the system can’t see beyond the established pattern. When faced with change, the response is often: “There isn’t my truth or your truth, there’s just the truth.”

But the reality is more nuanced than that. And that’s where strategic change planning comes in.

The Information Advantage

At Information Advantage LLC, we help organizations navigate the complex world of strategic change, innovation and culture by building strategies rooted in trust, clarity, and adaptability. Whether you’re combating misinformation, fostering resilient communication networks, or building a culture of transparency, we’re here to help you find your advantage in today’s dynamic information environment.

Let’s rewrite the narrative—together.